Tags

Related Posts

Share This

OPEN SKY

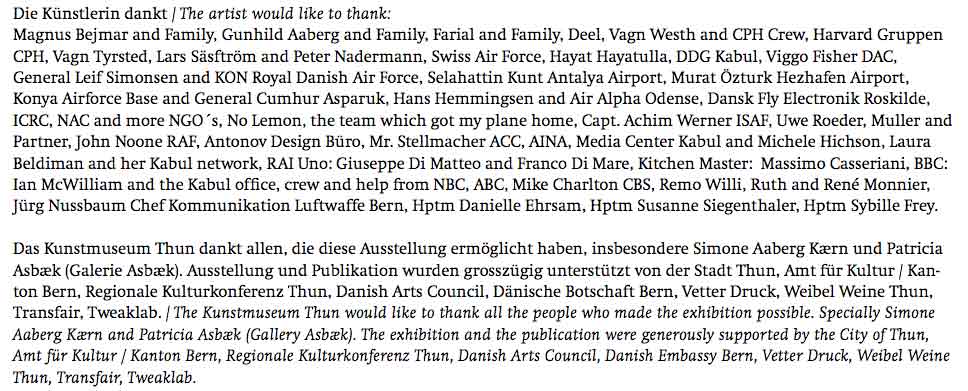

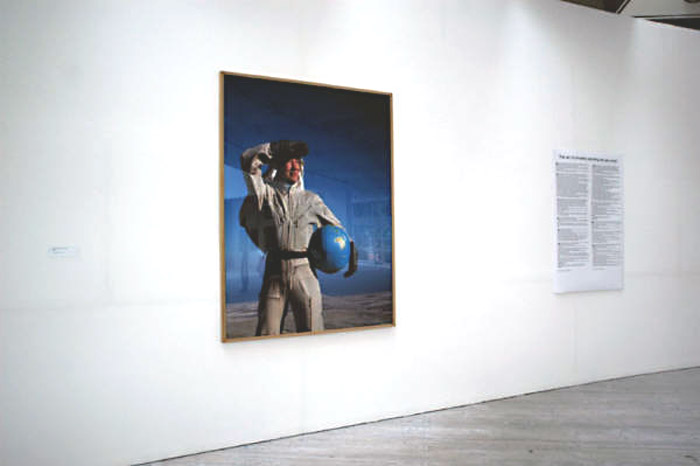

Installation view, Open Sky, Malmø Konsthall, Photo: Anders Jiraas.

OPEN SKY at Malmø Konsthall curated by Jacob Fabricius.

Simone Aaberg Kærn, in the early 1990s, began working with projects relating to surveillance and control. This, however, soon turned into a fascination for the unreachable and impossible task of floating: flying in the space. Through animated flying videos, such as Air (1994), wanna fly (1995), and Royal Greenland (196), Simone Aaberg Kærn investigated and soon found a symbolic free space in the air. At first, it was animated spaces, in which she flew across the skies of Copenhagen, New York and Greenland seeking the limits of gravity and individual unassisted human flight. Soon after Simone Aaberg Kærn achieved her own flight certificate in order to produce the work, Sisters in the Sky. This was demanded by Anne Noggle, one of the female pilots, who also was portrayed in the work Sisters in the Sky (1997).

Simone Aaberg Kærn’s painted portraits of female fighter pilots from Second World War was shown at and acquired by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk. Sisters in the Sky is an impressive aesthetic and intellectual peephole of how women at that time could realize their dream of flying in a time of hardship. In the painting and sound installation, Simone Aaberg Kærn narrated their stories with a poetic, political and feministic gesture and introduced the notion of aero feminism – an aero feministic sisterhood across cultures and generations.

One of Simone Aaberg Kærn’s most spectacular projects started in 2002. One day the artist read an article in a Danish newspaper about the girl Farial from Kabul in Afghanistan. Farial’s greatest wish was to become a fighter pilot. Simone Aaberg Kærn had no doubts; she had to attempt to reach her and show her how to fly.

In Micro-Global Performance (2002-03) Aaberg Kærn took off in her fragile Piper Colt flight from Little Skensved, Denmark, to Kabul, Afghanistan. Micro-Global Performance is produced in collaboration with Magnus Bejmar. They flew across borders; crossing the enormous mountain range Hindukush (the Hindu Killer) to Kabul with the risk of the American Air Force would attack them. In the film Smiling in a War Zone (2005) Simone Aaberg Kærn crosses war zones and defies the military power in order to make contact to the girl Farial. She risked her own life so she could give Farial a journey in the air. In the film Farial flies the plane over Kabul.

From a global perspective, the sky and the airspace are a place of battles – over power, prestige and politics. At the same time, the sky is a place of refuge for individuals, a place onto which you may project your own wishes and dreams.

by Lars Grambye, Jacob Fabricius & Lotte Petersen.

from the exhibition catalogue Simone Aaberg Kærn: Open Sky, Malmö Konsthall (Sweden) 2006

Used with permission of the authors and Galerie Asbæk

© The authors

“AIR” video installation Simone Aaberg Kærn 1994

“wanna fly” video installation 5 skærme med lyd, Simone Aaberg Kærn 1995

“Calling” video installation Simone aaberg Kærn 1994-2006

Royal Greenland, video 1995 Simone Aaberg Kærn

Sisters in the Sky, 45 paintings oil on canvas and sound insalled in curved corridor. Simone aaberg Kærn 1997 courtesy Louisiana Museum of modern art.

“Sisters of the Red Star” 3 channel video installation with sound 1998

OPEN SKY – signature photo for the project a-microglobal Performance. Simone Aaberg Kærn 1996

“Fragments from a microglobal performance” actual flying maps and large photos

Simone Aaberg Kærn 2002 -2006

“The Sisters From Mazar” Simone Aaberg Kærn 2003 -2006

“Freedom Fighters”

“SMILING IN A WAR ZONE” swedish poster

“Freedom Fighters”

The Art of Flying to Kabul

In 2002, the performance artist Simone Aaberg Kærn did what no one thought was possible, flying a small canvascovered plane 6000 km from Copenhagen to Kabul. FILM talked with Aaberg Kærn and co-director Magnus Bejmar about “Smiling in a War Zone – and the Art of Flying to Kabul”, an artistic statement about freedom sustained by the dream of flying.

Af Annemarie Hørsman

Publiceret i FILM #47, November 2005

It can’t be done, other pilots told Simone Aaberg Kærn and Magnus Bejmar. Even with a more modern plane and more money, we wouldn’t make it halfway, they said. The two of them nevertheless managed to make the remarkable journey, which they have now turned into a documentary.

“Smiling in a War Zone – and the Art of Flying to Kabul” is a modern fairytale about Aaberg Kærn’s stubborn struggle to build an air bridge across two continents. We follow her persistent negotiations with air traffic controllers and generals about airspace access, and we are with her in the cockpit when she finally takes off for Kabul, despite a definite no-go from the American Air Force. All this to give a girl in Kabul a chance to fly.

The dream of flying

For Aaberg Kærn, a performance artist, the right to fly is a crucial ideal of freedom. Her project emerged in the wake of September 11, when access to airspace was strictly cut back. “I have defined the air as my artistic field. The air should be free. We should be able to send our dreams up there and move around there freely. So I was thinking about how to make a project that would win back the air.”

One day in January 2002, as she was sitting in her usual café, she read an article about a girl in Afghanistan who wanted to become a fighter pilot so she could strike back at the Taliban. “All at once, several threads came together at a single point. I immediately knew this was my project. I wanted to go to Kabul and take this girl flying.”

She finally got underway on 4 September 2002. With her in her old Piper Colt ’61 came Magnus Bejmar, her boyfriend, codirector and cameraman. The flying theme has been an art practice and a productive creative utopia for Aaberg Kærn since 1996, when she began a project about American women pilots in World War II.

“I’m interested in what drives our civilisation. When you lie down and look up at the sky and you see the birds, you think, Wow, what if that was me up there? Basically, that’s what humankind has always been doing, in different ways, including the use of drugs. But it also means that we have always been trying to do something beyond what we are capable of. It’s a sign of the utopian, the sublime. Sometimes, the result is Stalin or Hitler, since destruction is an inexorable part of it. But it also makes room for creative utopians. Such a person was Otto Lilienthal (1848-96), the great German glider pioneer,” Bejmar says.

“Lilienthal proclaimed that everyone should fly, no matter what the cost. He constructed a pair of giant wings and made over 2,000 flights with them before it finally killed him. A few years later, all his data were read on the other side of the Atlantic by two bicycle smiths in Ohio, the Wright Brothers. They got a plane in the air and 66 years later man was walking on the moon. We must allow for creative utopians to have their dreams, if we want society to move on. Here’s this 16-year-old Afghan girls who dreams of becoming a fighter pilot. Just think if girls who take up flying in Muslim societies and end up starting a democratic development. You never know.”

Naivety as a tool

The thought of making a film came up early on in the project. It also quickly became clear that this should not be a traditional documentary. “We wanted to make a film that would evoke the same feelings as feature films that can make you a little sad, a little happy and maybe a little annoyed,” Bejmar says. “So we coined the term docutale. Reality told as a fairytale. Which fits the performance concept well, too: if you prod reality a bit by adding a new element to it, it shifts, which forces you to look at it differently. So it is with Simone, the flyer. She is the object we add to the world, that people have to relate to as we go along.”

The sequence about the flight to Kabul, in particular, displays the two directors’ whimsically playful filmic language, employing a wealth of musical pastiches, trick shots and archival footage. “The film is high-pitched from the beginning, as when Aaberg Kærn proclaims, ‘The skies must be free!’ That’s extremely important,” Bejmar says. “But at the same time it’s ludicrous, deeply comical. Here’s this one person in her little plane going up against the USA, telling them, ‘Don’t forget freedom, goddammit, now that you’re going to war!'”

“It provides some distance and also a smile,” Aaberg Kærn continues. “People love ‘The Little Prince’ for the same reason. This little character leaping out and getting a chance to make a statement in the space we’ve created. But by adding all these movie effects, such as a massive symphony orchestra out of 1940’s Hollywood, we show that we are playing, which in turn fosters discussion of the actual events in the film.”

For Aaberg Kærn, naivety is also an essential tool in even making the trip. “For me, it’s about using the sensation of falling in love as a spearhead,” she says. “You have to be pretty cynical and strategic to be able to carry out this kind of project, but it also has to be honest on a very basic level. It’s the same glow we have when we fall in love, a kind of madness, but it protects us. I’ve developed a method for putting myself in that frame of mind and switching it on and off when I set out to do something. “That way, naivety becomes a role – and a technique. It’s my performance character and it’s a technique that makes it possible for me to even finish the trip. But it’s also a technique in making the film, for taking you into the story up to the point where Farial first says hello.”

Aaberg Kærn and Bejmar finally touch down in Kabul’s airport on 6 December after a two-month journey. They meet the girl, Farial, but they also come face to face with traditional Afghan clan culture. Although they do manage to take Farial flying, the last part of the movie makes a virtue of showing utopia stranding on the beauty of its own idea.

“What interests me as an artist,” Aaberg Kærn says, “is taking an idea and confronting it with reality. In that meeting, things emerge. The main frame around the film is utopia hitting actual mud, real matter. We crash from 10,000 feet directly into the Afghan reality, which is tough and incredibly concrete. After all, it’s a pretty antisocial project, because we’re using Farial. When we first meet her, she is a pretty good sacrificial lamb, answering the requirements of my story. Then Afghan clan structures enter the picture and try to lock her down more and more the whole time we’re there.”

“As it turns out, there are already two sisters in Afghanistan who are helicopter pilots,” Bejmar adds. “We come to Afghanistan with a completely developed idea that Farial will be the first girl in that country, after the Taliban, to fly. Here we come with our artistic statements and our dreams, and then reality intrudes and pops the bubble. We could have edited that part out, but we think it’s kind of cool to be kicking ourselves a bit. Here we come and, hell, they’re already flying!”

Google Earth

Although the performance strategy isn’t new, this type of “extreme expressionism”, as Aaberg Kærn calls her method, can still challenge our notion of the clearly defined artwork. But for Aaberg Kærn, the distinction is insignificant. It’s more a question of scale. Her performance strategy is still a frame and, within it, she tries to create a dialogue. Similarly, the film is a frame that creates its own meaning, but it doesn’t contain the whole meaning.

“I want to ask the question of where the artwork lies, but not answer it,” she says. “When you sit in the cinema, you have to ask yourself if the art is getting Farial to fly, or what it means to use her for this purpose. That’s what I present.”

“The most interesting thing about the art space is that, because it’s still difficult to really define, it’s a space that has people’s ear. If it’s an artist speaking, a lot of people will be willing to listen, which offers opportunities for telling stories.”

“That’s also why art can hit entirely different targets than a political mission operating with a very obvious agenda. I’m not interested in providing any answers about what’s right and what’s wrong, because there is no simple truth. But it is interesting to make a statement that others can build on. I think the film is a good contribution to the debate about individual freedom, for instance, which is such an often-heard claim in our part of the world. But in a lot of other places, it’s not like that at all. There are good sides and bad sides to it.”

Meanwhile, Simone Aaberg Kærn and Magnus Bejmar hope their film will provide an elemental pleasure: the joy, beauty and freedom of flying your own plane. “We’re all sitting here now looking at Google Earth. That’s what we do in real life: go out and see the world from above,” Bejmar says. “If the film is able to convey even the slightest sensation of that, that would be great. Smile a little, live life, stop complaining. You can be upset about the war in Afghanistan or women’s rights and write a letter to the editor and sit in a café and mope for three months, but come on, do something, move in a different direction, make a difference!”

COSMO FILM DOC APS

Founded 2003 by Jakob Høgel, Tomas Hostrup-Larsen and Rasmus Thorsen. A sister company to Cosmo Film, the latter being now fully devoted to producing fiction. Cosmo Film Doc is specialized in creative documentaries for broadcast and cinema distribution in Europe. Aims at becoming a major European player in the field of internationally financed, creative documentaries.

SIMONE AABERG KÆRN

Born 1969, Denmark. Performance and video artist. Her work often includes the art of flying as a theme, as in “Taraneh Heading for the Stars” (2001), a dual screen video installation and short film, about Iran’s first female pilot and in “Sisters in the Sky” (1999) for DR TV. “Smiling in a War Zone” is her debut as a documentary film director.

MAGNUS BEJMAR

Born 1965, Sweden. Radio and TV journalist, has also worked as a director and writer for the theatre. “Smiling in a War Zone” is his debut as a documentary film director.

Contact Magnus Bejmar : at magnus.bejmar(at)hotmail.com

THE ART OF PRIVATELY PATROLING THE AXIS OF EVIL

| W |

hen all grounds of any interest are owned, controlled and lined up, the skies got to stay open!

The art project “1001 Nights 2002” has reclaimed the freedom of the sky.

It was an attempt to test if you can cross borders, flying yourself and manage as an individual to process

the massive amounts of red tape, combined with such an operation.

To obtain necessary permissions and fly, map in hand, looking out the side-window;

following rivers, roads and valleys along the border of Iraq right into Iran.

Crossing it and pursuing on a mission to reach Kabul, Afghanistan.

Claiming anyone’s right to the sky.

The freedom to fly anywhere at any time, even after 9/11.

It took off from a farmers grass strip in Denmark, at the 4th of September 2002.

| T |

hat was ten years after Rumsfeld, Cheney and Wolfowitz had published the first draft of “Space power theory”.

A document describing how air power can be used to control the grounds and how space power can control the air.

“Full spectrum dominance” is a key issue in this paper. Establishing USA as the only dominating power on the planet.

The “drone attack” in Yemen hinted towards the perspectives of full spectrum dominance.

To take out any target, anywhere at any time.

The war in Iraq showed it even more clearly, cruise missiles attacking top targets in Baghdad.

B-2 bombers taking off from fields amidst lands of genetically modified corn, flying

superdupersonic speed across the globe. Crashing the cradle of agriculture between

the Tigris and the Euphrates.

Finally ending that era of agriculture, establishing their new times.

A task obviously not fully understood nor challenged in a Europe lacking coherent space policy.

Staging an impotent war machinery.

Briefly addressed by Beijing’s declared will to reach the moon and a Russian hope to cling on to,

what was once a race, but now, is an established fact of domination of space-research.

| F |

ar eastern Iran, the holy city of Mashad.

Close to the Afghan border.

Three months on our way. The Americans controlling Afghan air space, denying us to enter.

Last words from the US Major on a hissing line to Qatar:

“Sorry to say Mam, but if you cross that line, you would be a target Mam. I repeat Target!”

Click!

Time passed by noon before we finally entered our forty-year-old Piper Colt.

The little two-seater wiggled out over deserted lands, once the route of silk caravans.

A line in the sand, clearly visible from 2500 feet.

The Afghanistan border.

Goodbye and good luck from Iranian air-defense radar control seventeen minutes ago. It didnÕt take long before the radio started to spark:

“This is area control. Aircraft crossing line, heading one, two, four. Identify! Identify!”

Like an invisible voice from the sky, the ever patrolling AWACS high up there somewhere. They spotted us immediately.

We penetrated American fortress Afghanistan.

“We no shoot you down! This is baby-plane, no danger!” the local commander

of Herat airport watch-group explained, pointing his Kalashnikov to the sky.

If you are small and persistent Ð you can succeed.

*

| K |

abul, on a mission amongst ruins to find a girl.

A certain girl, special, her name: Faryal, a 16-year-old with the outspoken dream of becoming a fighter pilot.

She told this to a Danish reporter, those hectic January days when reporters paid thousands of dollars to be driven around,

having women to unveil and shyly look out of their burkhas.

Now the reporters gone, the burkhas on.

Faryal still in school, now teaching the English she learned less than a year ago.

We found her.

Completing the “axis of meaning”Simone saw that grayish winter day over a cappuccino in her morning caf�.

The article was electric to her.

After the work “Sisters in the sky” about how women went into the field of military pilotry during WW II,

a link was there, the future in front of her.

Faryal facing much the same problems with cultural resistance as women did in the west not to long ago.

To take her flying, letting the controls to her over the ruins of Kabul. A wish for the skies would come true.

| M |

odus operandi being the one of aero feministic action.

Building a cross border, cross time, sister hood in the sky.

Using the full involvement technique developed in earlier works.

That is, to perform the task and persistently telling and retelling your story, letting every individual who wants to,

become a pillar in this imaginary air bridge between west and east.

Trusting their Yes! to open skies, making yet another leg closer to the goal.

Bringing courage from flying sisters along route.

There where the young Croatian girl, new at flight academy. The Turkish-Bulgarian, a Muslim, well on her way in the cockpits.

Turkish female fighter pilots of today, who flew formation with Simone in their F-5,”Freedom Fighters”.

| F |

aryal facing this sister hood was quite uninterested in them all.

She more bound to deny her dream, controlled by a mother obstructing possibilities for the daughter to lift from the ground.

We, a metaphor on how the west throws itself upon any prey in need to satisfy this thirst for righteous”good-willing”.

Faryal is tough, Afghanistan is harsh. Simone is determined.

Now cultural negotiation begins for real.

A Pashto clan leader helped as an intermediary.

Letters signed by ministers from Aviation and Defense Department provided security.

Cooperation with controlling Turkish forces made the actual flying possible.

Slowly Simone and Faryal could define themselves, sharing the same dream.

It took a month to do.

No more men, mothers or officials in their way.

They met on the ground, found a platform, made it closer to the plane.

Faryal finally took off. She steered the airplane out over Kabul.

She smiled, threw up, wiped off, laughed and flew on.

Ò1001 Nights 2002Ó succeeded in its claim for anyone to fly anywhere at any time.

No matter what.

The skies reclaimed!

Tin-tinism and postcolonial flair being a flirting bonus a year when aviation celebrates 100 years.

The Wright brothers took off 1903.

Where did it take us?

Simone Aaberg Kærn/ Magnus Bejmar